Global representations of Spanish cheeses are so often confined to Manchego. While this acclaimed cheese, in all its magnificent forms, has certainly earned its reputation, there’s much to be discovered outside of the La Mancha region; there’s cheese-filled culture and history in every corner of the peninsula.

Cheesemaking in Spain is an ancient practice: archaeologists found that styles of primitive cheesemaking existed in the Iberian peninsula since the Neolithic and Bronze ages. Yet the true drivers of the Spanish-style cheeses we know today were the Romans, who introduced techniques like smoking and oil preservation to the peninsula.

Cheesemaking and consumption became so prolific that in the 1400s the Spanish government began regulating the price of cheese. Spain, like many areas in the European Union, still continues to regulate certain cheeses, just as they do with wine and other food products. There are currently 26 cheeses throughout the country certified under these quality controls, known as “denominaciones de origen protegidas,” or DOPs.

Outside of DOPs, categorizing Spanish cheese isn’t simple, but Antonio Padilla, my local cheesemonger here in Seville, Spain, says that in the most basic terms, cheeses in Spain can be divided into three regions: cows in the north and the Balearic Islands, sheep in the middle, goats in the south and Canary Islands. There are certainly exceptions, but it’s generally consistent.

Thus, cheese consumption here in Spain, like most of the country’s food and drink culture, is hyper regional. Spaniards continue to eat foods that are tied to local production, and each region wears their individual food banners with pride. Here in the south, for example, it’s common to find cheese made from Payoyo goats on the menu, but they’d be hard to come by in the Basque Country, where Idiazabal cheese shines.

Last year Mat Schuster of Canela restaurant in San Francisco introduced us to Spanish cheeses that are definitely worth tasting. Here we’ll dive into even more to try on your next trip to the cheese shop, or get straight from the source in Spain.

Burgos

The city of Burgos makes all sorts of cheeses. But say “queso de Burgos” at a restaurant in Spain and you’ll be served a compact, fresh cheese far different from the bold, hard cheeses Spain exports.

Traditionally made with just sheep’s milk, cheesemakers play with hundreds of different varieties using goat and cow as well. Fresh cheese like this has a short expiration date, so you’ll need to head to Spain to get your hands on it.

“Cabrales y Sidra” by jlastras is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Cabrales DOP

The most well-known blue cheese in the country, Cabrales, is made in the Picos de Europa, or Peaks of Europe, specifically in the Asturias region. It’s made primarily from cow’s milk but you’ll find goat and sheep blends as well. Some styles of cabrales are aged in caves—Padilla says that’s how the best varieties are made.

Cabrales is an especially intense cheese that often pricks the mouth and begs for acidic beverages, like the dry cider consumed in the region.

Gamonedo DOP

More accurately known as Gamoneu in Bable (the regional language), this sharp cheese also comes from the Asturias region. “Gamoneu is one of the best cheeses in Spain,” says Padilla. It’s a blue cheese made from sheep, cow, and goat, and varies in both its sharpness and appearance depending on how long it’s been aged.

Traditionally, this cheese was made by shepherds, who lived alone with their herds in the mountains. They would hang up the cheeses and smoke them in their small cabins. This particular method is still utilized today, though there are also more modern methods available in the market.

“* Queso Idiazabal de Pastor” by Mumumío is licensed underCC BY 2.0

Idiazabal DOP

Idiazabal is a raw sheep’s milk cheese hailing from the Basque Country and Navarra. Idiazabal is made from either Latxa sheep or Carranzana sheep, both of which have iconically shaggy, mountain wool. Not all Idiazabal cheeses are smoked, but like Gamoneu, many shepherds would hang these cheeses from their cabin beams and smoke them.

Each wheel of Idiazabal must be aged a minimum of 60 days. With an intense and balanced flavor, and a compact, fatty texture, Idiazabal is incorporated into all kinds of meals in the Basque Country, from savory sauces to desserts.

“Quesos de Mahón” by M. Martin Vicente is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Mahón DOP

This raw cow’s milk cheese hails from the Balearic Island of Menorca. The Brits actually gave it its name: they invaded the island in 1708, started exporting the cheese, and called it Mahón after the port from which it left.

During the curing process, Mahón is wrapped in canvas cloth and suspended by its four corners with twine, producing a square form with rounded edges. It’s then rubbed with olive oil or paprika. Depending on it’s curing process, Mahón ranges from creamy and buttery to a hard and nutty.

“File:Queso Majorero en el Club del Queso de Mumumío de Diciembre 2011.jpg” by Mumumío (www.mumumío.com) is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Majorero DOP

Known as the cheese of Fuerteventura (a small island in the Balearics), Majorero’s name comes from the breed of goat used to make it: the Majorera. The island landscape is incredibly dry, and these goats feed on cactus and thistle, producing sweet and herbal flavors in this hard cheese. Though the Majorera goat makes up the majority of this variety, this DOP allows for the addition of Canary sheep’s milk.

Apart from the simple, natural style of the cheese, it’s also commonly covered with paprika or gofio, a toasted flour made of various grains originating in the Canary Islands.

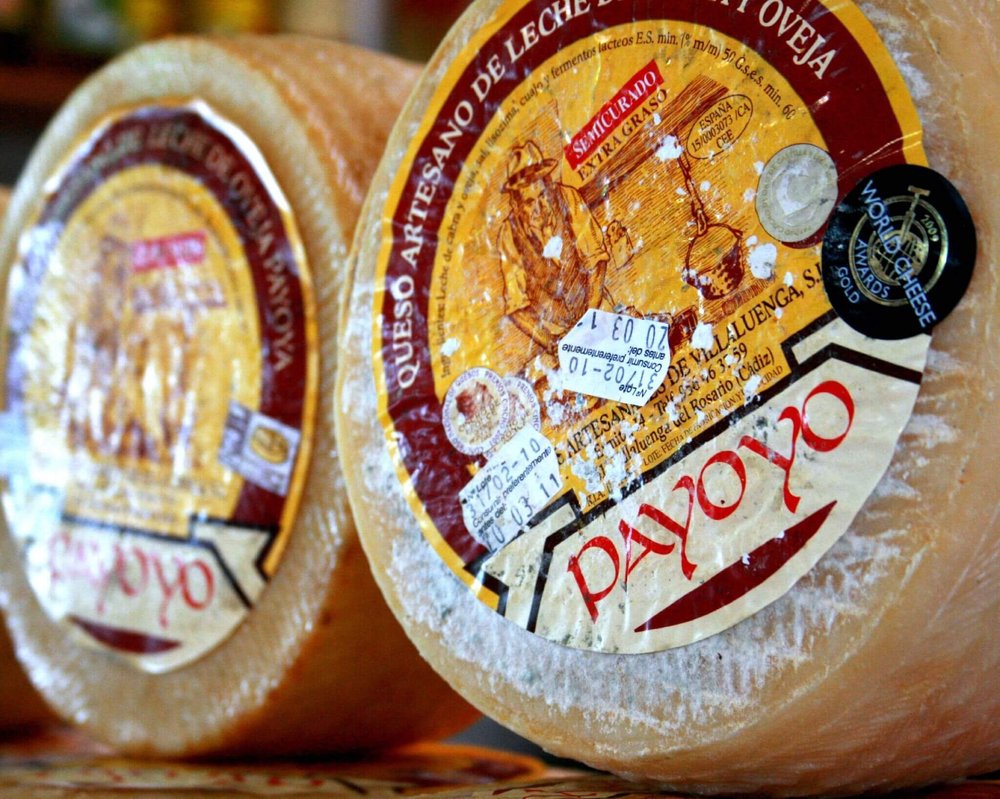

“Queso payoyo” by annalibera is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Payoyo

Technically, Payoyo is actually a brand of cheese made from indigenous Payoyo and Merina goats in the southern province of Cádiz. But the name has become associated with any cheeses made in the Sierra of Cádiz, most of which are made from Payoyo goats. It’s a bit confusing at this point, as there is not yet a DOP to regulate naming.

Thus, there’s quite a variety of “Payoyo” cheeses, from soft and ultra-creamy styles reminiscent of chèvre, to hard, aged cheeses with elegant toastiness. Cheesemakers are also experimenting with rinds bathed in rosemary, paprika, olive oil, and even local sherry wines.

“File:Queso tetilla entre otros.jpg” by Ardo Beltz is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Tetilla

This cheese gets its unforgettable name from its iconic shape: tetilla translates to “little teat” in Spanish. Legend has it that the people of Galicia (the most northwest autonomous community in Spain), having been forced to reduce the size of queen Esther’s breasts painted on a scene on cathedral portico in Santiago de Compostela, rebelled and decided to create a cheese in the shape of a voluptuous breast.

Tetilla is made from cow’s milk, and is creamy, light, smooth, and melts incredibly well.

“#LaMesaDeLaAntigua” by QUESERIA LA ANTIGUA is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Zamorano DOP

Zamorano comes from the province of Zamora in the Castille and León region of Spain and is made from two breeds of sheep, the Churra and the Castellana. Produced just next door to its famed neighbor, “Zamorano,” says Padilla, is what I would choose over Manchego.” It actually requires a longer curing period than Manchego’s 60 days, with a minimum of 100 days. This curing process yields warm, rounded flavors similar to that of Manchego. Pale yellow and crumbly, it has a distinctive zigzag pattern on the rind.